For 22 million people, the effects of climate change are already devastating. Mexico City is facing “Day Zero”, a time when water does not run anymore. Water would have to be transported physically by truck or car. It is on the list of the ‘top ten’ cities most likely to run out of water.

If the Republicans think there is a border crises now, wait until 20+-million people start looking frantically for water.

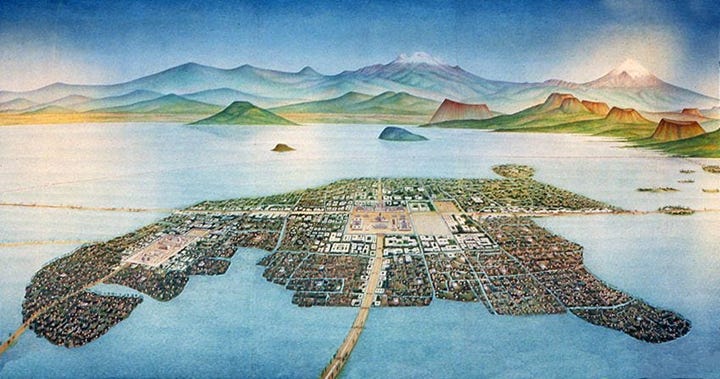

The situation is ‘unprecedented’ and has been building since the arrival of the Spaniards. Situated at high-altitude, it was once the location for the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan — a city founded on an island on Lake Texcoco and built outward through an ingenious network of canals, bridges and artificial islands.

After conquering Tenochtitlan in 1521, the Spanish tore down the city and drained its lake, founding Mexico City on the soft, clay-rich soil of the lake bed. They did not take precautions to manage the water as the Aztecs had done for nearly two centuries. Over the course of 400 years, canals were turned into streets, and rivers became part of the city’s sewer system. Where once there was a 2,000-square-km lake, there is now a modern city in all directions.

Centuries of over-pumping have led to the sinking of the downtown area — which sits 10 meters lower than when the Aztecs were in charge. This sinking, in conjunction with the geography of the city (which does not have natural exits for water inflows), significantly increases susceptibility to flooding. Despite billions of dollars invested in infrastructure, the city floods every year, taking a major toll on economic activity, damaging property, and causing substantial public health problems. Despite frequent downpours, only eight percent of annual rainfall recharges underground reservoirs, leading scientists to predict that this dangerous imbalance will likely leave the city dry in only eight to ten years.

One of my favorite stories of “advanced” improvements to an indigenous practice comes from Southeast Asia, where European experts arrived at an area that had particularly heavy rainfall. The natives were plowing the hilly fields in line with the drainage, so water was pouring off the fields down the furrows directly into a river below. Horrified at the thought of erosion, the Euro-experts immediately had the farmers plow at right lines to the water drainage, so the plow furrows would hold the water back.

The hold-back worked so well that one day, the entire farm field slid into the river. It was too heavy to grip the rock underneath.

The result of this kind of genius for Mexico City is a metropolis vulnerable to earthquakes, flooding and, from the destruction of its natural water cycle, droughts.

It is a crises that affects women in particular, because they are the ones who typically are in charge of running the household. In poorer areas, their lives start circling around these water issues.

Ironically, the city is not located in some barren dessert. There are times each year when the rainfall is apocalyptic. Floods can run on the streets for days. Mexico gets much more rain than a city like London.

Some residents are already dealing with Day Zero, as some areas no longer have piped water.

People have been dealing with this for five years in some areas. It means that they have to spend many hours of their day acquiring water. They wait a ‘water stations’ for deliveries that are inconsistent; they may be in line for hours.

“It’s an anxiety waiting to see if the water truck is going to come today,” said one resident.

Conditions in Mexico City are so bad that recently a rainwater catchment basin normally so green it’s used as a soccer field or for grazing animals, caught on fire, the Associated Press reported. Seventy-five acres of land were burned by the fire, with the Mexico City fire department saying the flames were brought under control by late afternoon.

It’s an “unprecedented situation,” Rafael Carmona, director of Mexico’s water system SACMEX, said, with a lack of rain being a major factor. Rainfall in the region has decreased over the past four to five years, he said, leading to low storage in local dams. A lack of overall water in the supply systems, combined with the high population, created “something that we had not experienced during this administration, nor in previous administrations,” he added.

These droughts have been getting longer and harsher, partly because of climate change and also due to this year’s El Niño climate pattern (which has boosted temperatures in the region and across Latin America).

Most of Mexico is experiencing some form of drought, with many areas experiencing the highest levels of “extreme” and “exceptional,” according to the country’s drought monitor. In October, 75% of the country was experiencing dry weather; the rainy season will not start until May.

Scientists predict there will be worsening droughts in the capital and north.

The Cutzamala System — made up of three dams and supplying 25% of the water consumed in the capital and almost half of that in the adjoining State of Mexico — is at 40% capacity, an historic low.

Last year was the driest and hottest since the 1940s, according to official figures, which meant reservoirs did not refill as much as usual. Authorities warn that if the Cutzamala System levels fall further, they could be forced to cut off supply entirely. As it is, they only have half of the water they received in 2019.

Affluent residents are blamed for making the situation worse. In Valle de Bravo, an area frequented by the wealthy, the giant dam that feeds water supply for roughly 6 million people in and around Mexico City is running dry, while hundreds of artificial lakes and dams — some only for ornamental purposes — remain filled on private properties in the area.

Climate change means there have been years of much less rainfall than normal. The former chief resilience Officer of Mexico City has warned that climate change is really the greatest risk to Mexico City.

“We’re extracting water at twice the speed that the aquifer replenishes. This is causing damages to infrastructure, impacts on the water system and ground subsidence,” said Jorge Alberto Arriaga, the coordinator of the water network for the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Roughly 60% of Mexico City’s water comes from an underground aquifer and the remainder is pumped uphill from outside the city. But the aquifer has been overused, causing the land to sink at a rate of around 20 inches (51 centimeters) per year since 1950.

The situation, which used to be confined to poor neighbourhoods, is now spreading.

“Even in a well-off neighbourhood, one day you go to your sink and there is no running water — no tap water…then you have to figure out ‘how do I acquire water?’ and what steps do I take?”

It has always been the case in Mexico that you cannot drink water from the tap.

People fill buckets with water from a tanker truck in the Azcapotzalco neighbourhood, as tensions over water scarcity in Mexico City, one of Latin America’s largest capitals, are boiling over and residents protest weeks-long dry spells in their homes, in Mexico City, Mexico on January 26, 2024 [Henry Romero/Reuters]

Mexico City’s residents know that on “day zero” the government will no longer be able to provide them with water. A city that was once built on water is now nearly dried up. How did this happen and what is being done to fix it?

There is a tangle of problems — including geography, chaotic urban development and leaky infrastructure — compounded by the impacts of climate change.

Drought conditions have prevailed across most of Mexico for several years.

Human-caused climate change intensifies evaporation, dries out soils and worsens droughts. Mexico has warmed about 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) since preindustrial times.

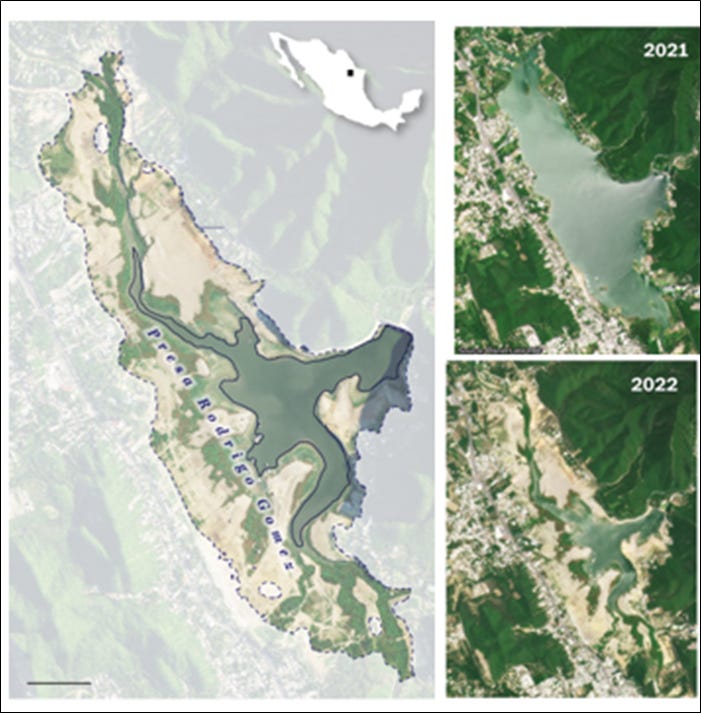

Water levels in the three dams that supply water to the city are dwindling. In July, level was so low in the Cerro Prieto reservoir that no water could be extracted. The Presa Rodrigo Gómez reservoir, commonly known as La Boca reservoir, is also nearly empty, as shown in satellite imagery at the top of the page and below. The reservoir near El Cuchillo Dam, which lies east of Monterrey, was at less than half-capacity a few weeks ago.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador acknowledged that growing industrial demand has strained water supplies and called on companies and farmers to give some of their water to the public during the drought. Heineken, the beer producer, offered some of its water allocation and donated a well.

Years of abnormally low rainfall, longer dry periods and high temperatures have added stress to a water system already straining to cope with increased demand. Authorities have been forced to introduce significant restrictions on the water pumped from reservoirs.

Mexico City gets its water from two sources: a system of reservoirs and underground aquifers.

The reservoirs are at historic low levels — well below 40% capacity — and the aquifers are over-extracted. The aquifer problem is due to climate change, in part, but also over-exploitation and the growth of the population itself.

Groundwater is also near record lows. The resource is used to supplement supplies when surface water is unavailable or running low, and it is overexploited during drought. It usually takes months to years to replenish.

The city developed in a very chaotic way. As new populations moved in, basic services like running water were not available.

The city Mayor assured residents that the water supply is guaranteed.

Yet an increasing number of residents depend on water delivered by truck, which costs $200 for a supply that will last 20 days.

The absence of rain is only one cause.

A study shows that 40% of the water supply is lost due to leaks in the pipes. Earthquakes have cracked some lines, and many pipes are more than 100 years old.

Money spent on water projects has decreased for many years.

Indigenous communities like Xoco have some large buildings like the “Mythical Tower’, which consumers five million litres of water a day. Residents there have not had a supply of running water in nearly a decade.

Indigenous champions say that they are attacked by the government for their stance as ‘water defenders’.

An interesting aspect to water is that it is a system, like a model of the ecosystem itself, and it shows how things are connected.

In the past, Mexico City was on a lakebed, somewhat like Venice, and all the smaller lakes and ponds were inter-connected. Then they were covered by roads.

Now there are new projects like “water capture”. Rainfall is captured from flow off the roofs of homes and purified at source. It is clean and it is free. Every square metre of roof can capture 7–8,000 litres of water each year. A small house can obtain 100,000 litres of water per year.

The problem of course is that few people have the storage capacity to save that much water. Those that do can solve their water problems for 6–8 months. That eases the pressure on water extraction and water purchasing.

The government plans to install 100,000 of these systems this year.

If that problem could be solved, Mexico City could get some 20% of its water from rainfall.

The system is being extended to schools; children are now told on some days that they have to go home, because there is no water in the school. One of the weaknesses of course is that rain is not a scheduled event. There is a season for it.

Which brings in the concept that the water shortage makes people stop and think about life and our place in the environment. Change is hard, especially when it depends on small-scale personal measures like water capture.

Going forward, the G20 Climate Risk Atlas shows that without urgent action, heatwaves will last 4005% longer — driving 34% longer agricultural droughts. The combination of sea level rise, coastal erosion and fiercer weather will cause chaos for Mexico’s economy, which stands to lose around 1.97% of GDP by 2050.

Mexico City will never return to its past as a city in a lake. But it can find a new water model, with rivers, small lakes and enough water for everyone.

L.A., Cape Town, Sao Paulo, and a growing list of other cities find themselves in Mexico’s plight.

Without water, they have nothing.

And if climate change continues to add heat year-after-year, the crises becomes a catastrophe.

While the remediation of climate change requires a full-society response, Mexico City shows that there are solutions on a small-grain scale that will help alleviate the water problem.

The trick will be working together to make it happen for all of us, instead of establishing ‘safe zones’ for wealthy inhabitants.

Because there is nothing safe in a society where people can’t get an essential ingredient of life.

Perhaps the water crises will be the lever that demonstrates to everyone the urgent need to work together on climate change. Your neighbor’s weather is your weather; your water is your neighbor’s water.

Can’t say it simpler than that.

People looking for a good visual explanation of the global environmental crises could go to this series of charts by Alvin Urquhart, Emeritus Professor and a founder of the Environmental Studies Program, University of Oregon. It is posted on the site of Job One For Humanity, a not-for-profit organization.

https://www.joboneforhumanity.org/a_short_illustrated_explanation_of_the_global_environmental_crises

Written by Barry Gander

A Canadian from Connecticut: 2 strikes against me! I'm a top writer, looking for the Meaning under the headlines. Follow me on Mastodon @Barry

Showing 2 reactions

Sign in with