A Master Class on the impact of climate warming is being taught daily along the Panama Canal. Consumers everywhere are going to feel the impact.

Much has been written on the impact this climate change is having on flooding, droughts and subsequent food supplies — not to mention extinction.

One field that has not received sufficient attention, is the impact that drought is already having on the world’s shipping routes. Over 90% of traded goods are carried over water. The volume will triple by 2050 as demand increases.

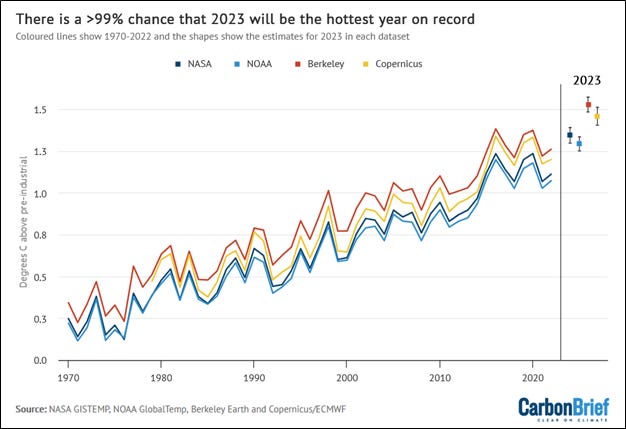

The climate threat to this traffic is real. Last year was the sixth warmest year since global records began to be kept in 1880. This year could be worse.

Those records note that the warmest years ever recorded have happened since 2010. If this year stays on track — and there is a 99% chance that 2023 will be THE warmest yearever — we will have lived through 11 of the warmest years since records were kept.

In other words, 85% of the weather since 2010 has been record-breaking in the worst possible way.

Climate change will affect ocean-going traffic in many ways, not least because the new hurricanes being spawned are coming closer to shore, necessitating the expenditure of tens of billions of dollars on port refitting.

Ironically, the shipping industry has been one of the major contributors to carbon emissions. It has now agreed to a net zero goal by 2050.

Focussing on shipping through inland freshwater connections, we can see a disturbing threat coming to major trade routes.

Connectivity matters in trade. The odds are that many of the goods in your home spent some time in the Panama Canal. Fresh water connectivity has declined dramatically over the past century. Primarily due to dam construction, two-thirds of large rivers around the world are no longer free-flowing. Reservoirs now trap approximately ¼ of the global annual flux of sediment — sediment that would otherwise reach deltas and the ocean. They also block the migration of fish.

But climate change blocks more than that. Climate change — in the form of lower water levels — also blocks trade.

“Climate scientists have long predicted increasing transportation disruptions and delays in global trade because of intensifying climate change consequences,” said Lawrence Wollersheim for the climate change think tank Job One for Humanity.

These climate-related transportation disruptions will cause ever-increasing shortages and delays in receiving critical and non-critical supplies worldwide.

The climate change-driven weather extremes that will cause these disruptions and delays are droughts (lowering water levels in crucial waterways), heatwaves, heat domes, wildfires, hurricanes, cyclones, tornados, floods, flooding, sea level rise, rain bombs, wind storms [Derechos], dust storms, wildfire smoke events, unseasonable cold spells, and other abnormal, unseasonal, or record-breaking weather.”

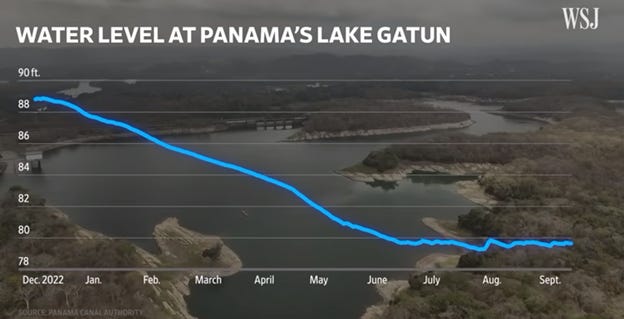

The Panama Canal, for example, handles about $600-billion in merchandise through its waters each year. It handles 55% of all the containers that go to the US from Asia. A full 6% of all global shipping goes through the canal. The ships make 14,000 transits per year. Every ship uses 52 million gallons of fresh water from Panama’s lakes, rivers and streams to make use of the raising and lowering cycles in the locks that raise the ships 85 feet and then lower them again.

The volume of traffic has been reduced from 36 ships to 32 ships per day. Additionally, some ships have had to reduce their cargoes by up to 40% in order to avoid grounding in the shallower lakes. All this at a time when there is skyrocketing demand for consumer goods.

And when the ships go through, they use an amount of fresh water each day that could have satisfied the needs of half of the country’s population for a year.

Rainfall in this normally-wet equatorial country has been 30 percent below average this year. This has dropped water levels in the two lakes that feed the canal’s locks.

The country’s leaders are considering options to improve the situation. One is the construction of an additional reservoir, which would cost $300 million and require the acquisition of protected land.

Because the Canal was built so long ago, Panama has rainfall records going back some 140 years. It gives planners confidence that the low-rainfall situation that they are now grappling with is a permanent shift. It is consistent with almost all of the climate change models.

Leaders know they have to make changes because the Canal will not fill itself.

If ships are forced to find alternatives for the Canal, they might try the Arctic route…which would present its own brand of environmental consequences.

Another option would be for ships to go from Asia to Europe and America through Egypt’s Suez Canal.

The Suez Canal has its own problems due to climate change.

Egypt is suffering from increased desertification and drought, and an increase in the intensity and frequency of sandstorms. Compared with today, extreme heat events reaching 45°C double by 2050 and are likely to increase seven-fold by 2100.

By strange chance, I was once in the Middle East on a patrol boat as part of a film crew. A dust storm blew up in the desert. It carried out to sea, and made the atmosphere look like we were inside a giant pumpkin. Everything we filmed was surrounded by an orange haze. No one would ever believe it was real, so we had to scrap the film footage. But it did show me how dangerous the desert wind can be, even when you are out at sea.

In May 2021, a cargo ship in Suez called the Ever Given was buffeted by unusually high winds. Its shape acted like a blocky sail and it ran aground in the winds that exceeded 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph). Combined with the varying depth of the Suez Canal grounding can become a significant risk. As the canal facilitates almost 10 billion of goods daily, resulting the six-day blockage caused by the Ever Given is estimated to have resulted in US$60 billion of disrupted trade, and the subsequent trapping of an estimated $700 million of cargo.

Climate risk near the Suez Canal also includes coastal inundation. An estimated 80%of world ports are in danger of a sea rise of more than 1 metre before 2080. Without considerable adaptation, these ports could become global ‘pinch points’ in world trade.

In Europe low water levels have caused heartburn over several years. Last summer, the Rhine, Europe’s busiest commercial waterway, was at record lows. This hurt shipping and deliveries to factories. It also caused the price of petrol and heating oil to rise. A lack of snow in the Alps is threatening to create the same problem again this year.

Shipping volumes on the Rhine had been consistent for the past 20 years, but since 2021, the level of water has triggered a drop year over year.

Switching to other modes of transport would be expensive and an even greater affront to climate change protection. A large Rhine barge can carry around 2,700 tons of freight, which would take more than 100 large trucks to transport.

Maritime navigation authorities are considering countermeasures for the Rhine like deepening the river in places. Another, much more expensive solution, would be to build dams that could be used to maintain or increase water levels in important sections of the river. Redesigned vessels and predictive software are some of the ways the supply chain is attempting to deal with the problem.

As European water levels drop, historic references to other times of hardship are revealed. “Hunger stones” emerge from drying riverbeds, with carvings warning of disaster if water does not return. In Decin Czechoslovakia a boulder that is central Europe’s oldest hydrological marker is now fully exposed; the oldest visible marking is from 1616.

The drying has made other historic relics come to life. In Lombardy, Italy, timber building foundations dating back to the bronze age have risen from the bed of the River Oglio, while the 100,000-year-old skull of a deer and the remains of hyenas, lions and rhinos have appeared on dried-out parts of Lake Como.

Across the world in China, due to unprecedented drought, water flow on the Yangtze River is more than 50 percent below average. The Yangtze is the world’s third largest river, and its most heavily trafficked waterway.

The Yangtze has almost completely dried up in some places. State media have reported that shipping routes in the middle and lower sections have closed.

It also provides drinking water to more than 400 million people and has threatened hydropower for large regions of the Chinese population.

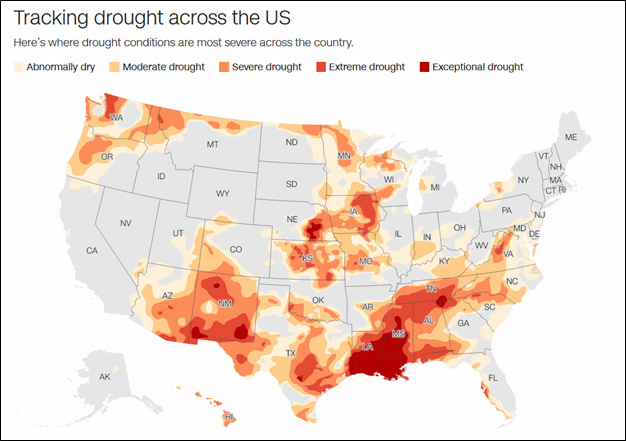

A great drying has hit inland US regions as well. Around 80% of the country’s surface is experiencing abnormal to moderate dryness.

The western part of the U.S. is undergoing a double whammy. Dryness is being accelerated by high temperatures, implicitly by global warming. The second hit comes from a lack of rain. Certain parts of the US have been in a moisture deficit since the start of the century, even though the country has been exposed to wet years in 2017, 2010, and 2005.

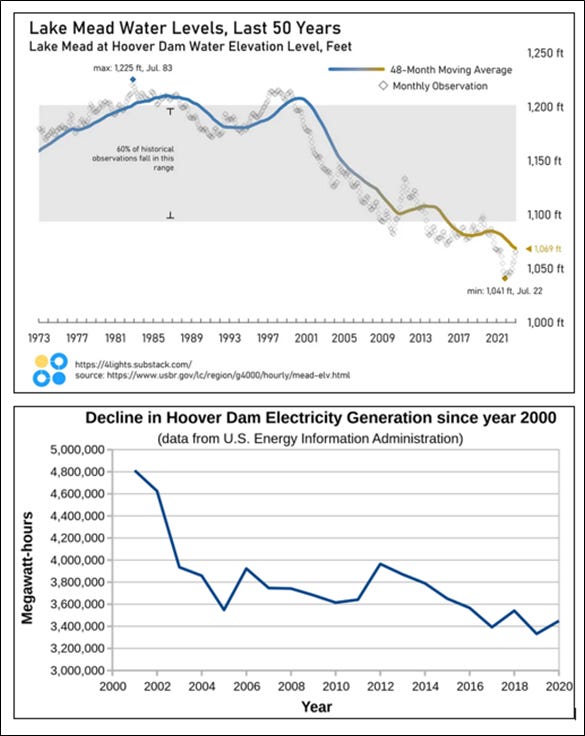

Lake Mead, which has been used as an indicator of climate conditions, remains at critically low levels despite receiving an influx of water from snowpack melt. It is still at only 30% of capacity, threatening the 25 million people who live in the Colorado River Basin.

Where this drying meets transportation, is along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. According to Bloomberg: “The Mississippi and Ohio rivers and their tributaries are major US freight arteries for moving coal, oil, natural gas, chemicals and commodities.”

The low water level in the Mississippi especially could cause a major financial impact. All the water level gauges along 400-miles of the river from the Ohio River to Jackson, Mississippi, are at or below the low-water threshold.

This comes on top of a drought from last year.

As water levels drop, the number of places where boats can be moored or accessible shrinks. Saltwater intrusion is also growing in Louisiana, as ocean water pushes up-river into drinking water systems.

The US Corp of Engineers is dredging the lower stretch of the river. The low water level has been preventing hundreds of vessels from passing through. All this causes the cost of transporting the harvest to jump. Lighter barges are needed to achieve floatation, and this means more trips using more fuel, so costs add up as do carbon emissions.

In all US inland waterways, about 578 million tons of cargo is shipped annually, with much of that along the Mississippi system.

Transport restrictions are a concern for barge companies and a heart-felt worry for the farmers who have just been through drought conditions. Now they will face higher transportation prices; about 60% of US grain exports are taken by barge down the Mississippi to New Orleans.

Also threatened by climate change are the 20 million people who use daily drinking water supplied with the help of the Mississippi River.

In its outlook for the coming winter, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists said they expect drought conditions to worsen in the lower Mississippi Valley, with the climate pattern known as La Niña expected to bring dry conditions to the southern tier of the United States.

The grim consequences of drought extend beyond a simple calculation about lower food supplies.

Drought means we cannot trade, either within our regions or around the globe.

Water runs our world. Climate change is showing that in a vivid and painful way.

Written by Barry Gander

Barry is responsible for all images and content.

To help do something about the climate change and global warming emergency, click here.

Sign up for our free Global Warming Blog by clicking here. (In your email, you will receive critical news, research, and the warning signs for the next global warming disaster.)

To share this blog post: Go to the Share button to the left below.

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with